- Examination of Neck Veins – Venous Pressure

- Examination of Neck Veins – Venous Waveform

History

Neck veins were first associated with heart disease in 18th century by Morgagni. Though venous waveforms were extensively described by Sir James Mackenzie in early 20th century, venous pressure on the other hand was largely ignored.

Venous pressure measurement was possible only after discovery of direct antecubital veins cannulation and use of glass manometer. Ernest Starling in 1912-1914 first investigated a link between venous pressure and cardiac output. In 1920s beside venous pressure estimate became a routine clinical practice, guiding treatment of heart failure.

In 1930 Sir Thomas Lewis, British cardiologist and student of Mackenzie, introduced simple bedside examination method that is still used today. It’s sometimes referred to as method of Lewis (see below).

Clinical Vignette

A 65-year-old male presented with dyspnea and abdominal girth grow for 1 month. His dyspnea is worse at night and on exertion. He denies chest pain, cough, sputum. He use to drink 4 beers per week. On physical examination, his blood pressure is 130/90 mmHg and has sinus rhythm, 80 bpm. Abdomen is distended. He also has mild pedal edema.

Next, you want to examine jugular neck veins to determine cardiac cause.

Physical Examination

- Room and patient setup. Have the patient lying supine on the bed, relaxed. Head of the bed can be elevated to 30° although adjustments (to more supine or upright) may be needed later on. The room should be well lit.

- Expose the neck. Ask the patient to turn head to the left so right side of the neck is exposed. Although venous pulsations can be visualised on both sides, left neck veins can sometimes have increased pressure due to disease in mediastinum.

- Identify pulsation. First try to identify any pulsation, then try to differentiate whether it’s arterial or venous. Venous pulsation has downward trend, have two pulsations per systole and changes with abdominal pressure or positioning of the patient. Arterial has upward movement, is easy palpable and does not change with pressure or position. Other characteristics are shown in a table below. Both internal jugular or external jugular vein can be used to determine the venous pressure.

- Estimating venous pressure. Identify highest point of venous pulsation during expiration (see Caveats and Errors). Then measure vertical distance from sternal angle to the horizontal line crossing the highest point of pressure. Add 5 cm to the measured distance (for example, 4 cm from sternal angle to the highest point + 5 cm = 9 cm of estimated CVP).

| Venous pulsations | Arterial pulsations | |

| Character of movement | Descending and inward | Ascending and outward |

| Palpability | Barely or not palpable | Easily palpable |

| Occludability | Easily occludable by light touch | Occludable only with hard pressure |

| Number of pulsations per cardiac cycle | Two | One |

| Change with respiration | Decrease during inspiration; increase during expiration | Does not change |

| Change with abdominal pressure | Temporarily increase during pressure | Does not change |

| Change with position | Increase with lowering the patient, decrease with sitting the patient up | Does not change |

Alternatively, central venous pressure can be estimated using patient’s hand, as shown on video below. However, it remains a rough estimate and more focused examination detailed above should be used.

Interpretation

Jugular venous pressure (JVP) is indirect measure of central venous pressure (CVP) which represents mean pressure in vena cava or right atrium. It can be expressed in millimeters of mercury (mmHg) or, more commonly at bedside, in centimeters of water (cm H2O).

Bedside examination can accurately estimate central venous pressure. However, measurements of CVP are only as accurate as external reference point chosen for the physiologic zero point (point of zero venous pressure in right atrium).

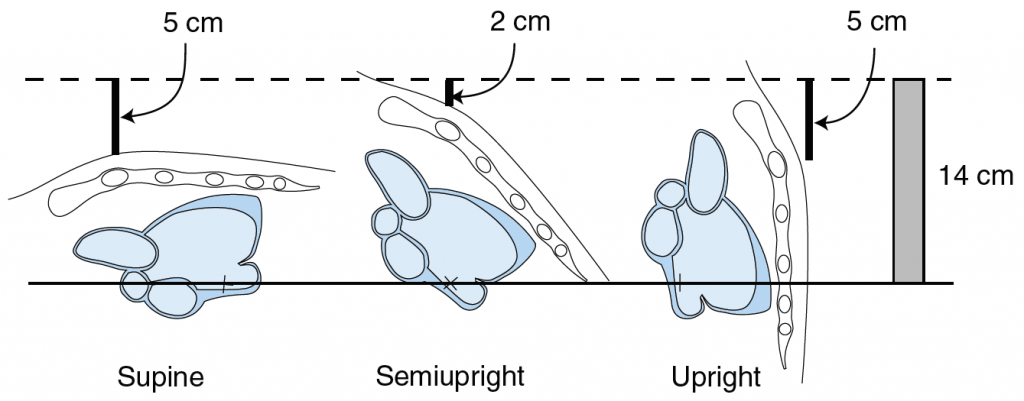

Reliable and accurate external reference point is sternal angle (angle of Louis) that Sir Thomas Lewis used for his bedside examinations. Physiologic zero point lies (more or less) 5 cm below sternal angle whether the person is supine, semi-upright or upright.

In method of Lewis central venous pressure equals vertical distance from the sternal angle to the top of distended neck veins plus 5 cm. For example: 4 cm (above the sternal angle) + 5 cm = 9 cm H2O. Studies have found out that bedside measurements or CVP are within 4 cm of water compared to invasive techniques 85% of time.

Central venous pressure is elevated if top of the neck veins in expiration exceeds more than 3 cm in vertical line above sternal angle, or if CVP exceeds 8 cm using method of Lewis.

Caveats and Errors

Patient position. Patient should be positioned to whatever level top of neck veins is best visualised. It may be supine, semi-upright in 30 or 45 degrees or even upright.

Jugular vein to use. Although traditionally taught to use only internal jugular vein, both internal jugular or external jugular vein can be used to determine the venous pressure.

Error in measurements & External reference point. Studies have found that bedside estimates of central venous pressure are accurate within 4 cm of water in 85% of time. As shown in image below, external reference point tends to change with patient position. Even though venous pressure is 14 cm of water, bedside estimate can vary from 10 cm (5+5 cm) to 7 cm (2+5 cm) of water, depending on position of the patient. Venous pressure increases during expiration and decreases during inspiration. Therefore measurements during expiration tends to minimize this error.

Courtesy of McGee and Elsevier. From McGee, S.R. (2018), fig. 36.2. See references below.

Clinical Significance

To be added at later date.

References

Chi, J., Artandi, M., Kugler, J., Ozdalga, E., Hosamani, P., Koehler, E., … Verghese, A. (2016). The Five-Minute Moment. The American Journal of Medicine, 129(8), 792–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.02.020

McGee, S. R. (2018). Evidence-based physical diagnosis (4th edition). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

McGee, S. R. (1998). Physical examination of venous pressure: A critical review. American Heart Journal, 136(1), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-8703(98)70175-9

Neck Veins & Wave Forms | Stanford Medicine 25 | Stanford Medicine. (n.d.). Retrieved 6 June 2018, from https://stanfordmedicine25.stanford.edu/the25/nvwf.html